I write this piece with the sounds of excavators and dump trucks in the background, as we are getting the 30-year-old pool at our house replaced this month. Pools should last a lot longer than that, but the original owner of the house decided to save money by installing the pool on top of a pile of logs and stumps left over from clearing the land. As those logs settled and decayed, the pool began to leak and we are left with a sizable bill to dig everything out and do things right. Even though we budgeted for this, it is still painful to see every load of junk exit and every load of gravel enter what I am calling the money pit.

On the higher education front, it has been a week with several announced or threatened closures. On Monday, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee announced that it would close its Waukesha branch campus, marking at least the fourth of the 13 former University of Wisconsin Colleges to close in the last several years. Fontbonne University in St. Louis also announced its closure on Monday, although they get a lot of credit from me for giving students and at least some employees more than a year to adjust. Today, Northland College in Wisconsin announced that it will close at the end of this academic year unless they can raise $12 million—one-third of their annual budget—in the next three weeks. Closures just keep dripping out, and I am really concerned about a late wave of closures this spring once colleges finally get FAFSA information from the U.S. Department of Education.

The two topics blended together for me (along with my students’ budget analyses being due on Friday) on my run this morning, and I quickly jotted down the gist of this post. The coverage of both Fontbonne and Northland focused on the number of years that they had lost money, so I used IPEDS data to take a look at the operating margins (revenues minus expenses) private nonprofit colleges for the past ten years (2012-13 to 2021-22). This analysis included 924 institutions in the 50 states and Washington, DC and excluded colleges with any missing data or special-focus institutions based on the most recent Carnegie classifications.

You can download the dataset here, with highlighted colleges having closed since IPEDS data were collected.

The first thing is that the share of colleges with losses varied considerably across years, and a high share of losses is driven by investment losses. But with the exception of the pandemic-aided 2020-21 year, the next lowest year of operating losses was 2013-14 (9%). 2021-22 saw two-thirds of colleges post an operating loss as pandemic aid began to fade and investments had a rough year.

| Year | Operating loss (pct) |

| 2012-13 | 11.8 |

| 2013-14 | 9.1 |

| 2014-15 | 31.6 |

| 2015-16 | 56.2 |

| 2016-17 | 12.8 |

| 2017-18 | 20.4 |

| 2018-19 | 37.2 |

| 2019-20 | 43.8 |

| 2020-21 | 3.5 |

| 2021-22 | 67.2 |

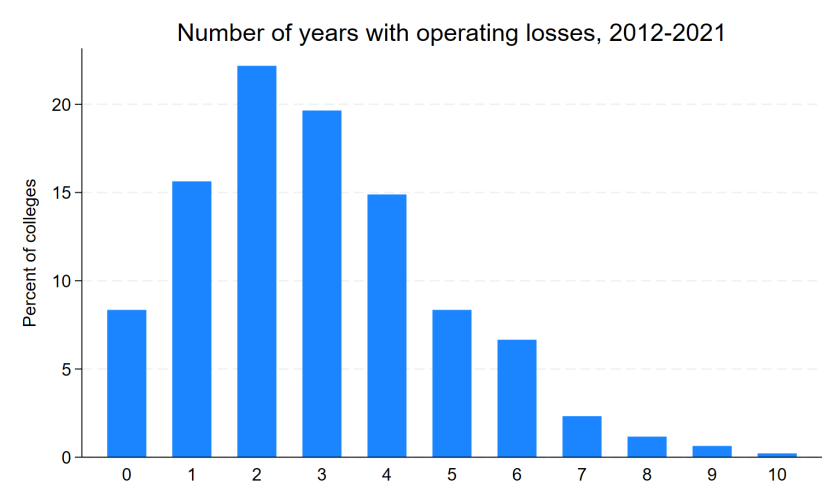

Below is the distribution of the number of years that each college posted an operating loss. Seventy-nine colleges never lost money, and most of these institutions have small endowments but growing enrollment. The modal college had an operating loss in three years, and 90% of colleges at least broke even in five years out of the last decade.

On the other hand, 19 colleges posted losses in eight or more years. Notably, nine of these colleges have closed in the last year or so, compared to nine of the other 905 colleges. (Let me know if I’m missing any obvious closures!) The list of colleges with eight or more closures is below, and closed colleges are highlighted.

| Name | State | Losses |

| Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico-Orlando | FL | 10 |

| Roberts Wesleyan University | NY | 10 |

| Trinity International University-Florida | FL | 9 |

| Iowa Wesleyan University | IA | 9 |

| Cambridge College | MA | 9 |

| Fontbonne University | MO | 9 |

| Medaille University | NY | 9 |

| Bethany College | WV | 9 |

| American Jewish University | CA | 8 |

| Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico-Miami | FL | 8 |

| Hawaii Pacific University | HI | 8 |

| Great Lakes Christian College | MI | 8 |

| Alliance University | NY | 8 |

| Cazenovia College | NY | 8 |

| Yeshiva University | NY | 8 |

| Bacone College | OK | 8 |

| University of Valley Forge | PA | 8 |

| Cardinal Stritch University | WI | 8 |

| Alderson Broaddus University | WV | 8 |

On a related note, I wrote a piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education that reviews a new book that makes the case for more colleges declaring financial exigency in order to cut academic programs. I think that it is more important than ever for faculty, staff, and students to have a sense of the financial health of their college by being equipped to read budget documents and enrollment projections. That is crucial in order for shared governance to have a chance of working in difficult situations and to help avoid money pit situations like the one in my own backyard.

Robert, Gary Stocker (College Viability App) would be a great person to interview about this.

If Wells College had to close, who is safe?

https://www.highereddive.com/news/wells-college-closure-end-of-the-spring-term-semester-abrupt/714628/

According to Kelchen’s database, Wells College wasn’t even close to closing — in fact, its 3 yrs was the “mean”!

Is the problem with the metric, or are other parameters more important?

It looks like they probably could have struggled through a couple of more years based on their financials. It’s interesting that they made a decision that quite a few other leaders probably wouldn’t have done.

It also highlights that while there are quite a few colleges with at least some risk of closure, it’s hard to perfectly identify which ones are closing in the near term.

Yes, hard to identify which ones are closing in the near term.

These are some of the parameters involved with increased risk of closure.

All these factors are relevant across the institutional field, but specific to individual colleges unique ways. I would argue that stratification and competition link closely with prestige and status factors (size, brand, location, endowment, etc.). Even HCM2 could be viewed as a catastrophic “unexpected event” in the regulatory environment.

Another distinguishing characteristic for institutions with increased risk of closure is for-profit colleges, and non-profit colleges that were formerly for-profit.

Here are some studies of what it takes to close down a college.

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/Products/Region/midwest/Ask-A-REL/10297