Colby College in Maine has promised the Class of 2029 that middle-class students who enroll will find their private liberal arts degree more affordable than many in-state public institutions. Thanks to a $10 million gift, the university has declared it will cap its tuition, room and board at various income levels; families making $200,000 will not see a bill exceeding $20,000 each academic year. President David Greene believes the financial aid package will help “families on the higher and lower ends of the middle-income spectrum who’ve fallen between the cracks and are left behind.”

Greene’s comments shed light on a more significant issue across higher education. As institutions increase their need- and merit-based scholarships to assist families from opposite ends of the economic spectrum, students in the middle are left with fewer options—and higher bills.

“The college tuition conversation can be a tough one for many middle-class Americans whose family income sets them above the threshold for the Pell Grant but isn’t enough to answer the affordability question,” Ken Woods, interim vice president of enrollment at Whittier College in Southern California, said in an email.

Private non-profit universities have a higher chance of experiencing the “barbell effect,” disproportionate enrollment of low- and high-income families. Middle-class families are more likely to pay for a public university tuition than estimate what they can afford to pay elsewhere, said Woods.

Institutions aiming to generate socioeconomic diversity at their institutions by prioritizing “low-need and no-need” families squeeze out students located somewhere in the middle, says Art Rodriguez, vice president and dean of admissions and financial aid at Carleton College (Minn.).

“There is socioeconomic diversity, but there isn’t a strong representation of what might be defined as middle-class students,” he says.

The Pew Research Center classifies middle class as having income between two-thirds and twice the national median income: $67,819 to $203,458.

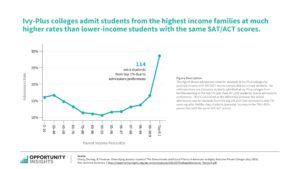

Ivy League-Plus institutions appear to have a horseshoe curve around their admitted students, permitting a 15% or higher admission rate for students whose parent income percentiles fall below 40% or higher than 99%, according to a report from Opportunity Insights, a nonprofit Harvard-based thinktank. The top .1% had a nearly 30% admission rate, which caught headlines as its publication coincided with the end of affirmative action.

More from UB: The 5 subjects proven to give undergrads the best wage premium

Carleton committed to enrolling low- and middle-income families in 2012. First, they pledged that at least 30% of each incoming class was made up of middle-income students, which it defines as those making between $40,000 to $170,000. Secondly, the university meets 100% of students’ demonstrated need for all four years if they qualify for need-based financial aid, says Rodriguez.

Universities can also adjust the specific factors used in calculating expected family contribution, such as by removing home equity from financial aid calculations, Paul Dieken, director of financial aid at Pomona College in California, said in an email.

Pomona is a need-blind school, meaning that it does not consider students’ financial contributions when evaluating their applications. Carleton, however, takes students’ ability to pay into account to ensure that at least some of its students can help yield tuition revenue, Rodriguez says.

New FAFSA guidelines might guarantee that the families of middle-class students applying to public universities might feel more of the weight of a college degree. Specifically, while it expands the number of Pell Grant recipients and the aid awarded, families will no longer benefit from the sibling discount. Consequently, middle-income families with two children will see out-of-pocket payments double, USA Today reports.

“You’re going to see most families aren’t aware this is coming and they’re going to be shocked when they see how much they’re expected to pay,” Robert Falcon, owner and sole proprietor of College Funding Solutions, told USA.

Is aid a zero-sum game?

California expanded its Middle-Class Scholarship program by $227 million in its past budget cycle, which awarded $2,800 to students whose families earn between $150,000 and $200,000, CalMatters reports. However, the Institute for College Access & Success (ICAS) disapproved, citing that it provides only half of that amount to students whose families are making less than $50,000, many of whom enroll in underresourced community colleges.

The concerns ICAS aired extend to the persistent issues low-income students put up with in pursuing a four-year degree. Over the past 10 years, studies show that the nation’s most selective colleges have decreased their percentage enrollment of first-year students eligible for the Pell Grant by 2%. Only 6% of Pell Grant recipients come from families earning $60,000 or more a year, according to the Education Data Initiative. Over half (51%) of all Pell Grant funds go to those whose families earn less than $20,000 annually.

However, Dieken does not believe access and affordability is a zero-sum game; middle-class students should apply before getting intimidated.

“The idea that providing more aid to low-income students somehow hurts middle-income students,” said Dieken. “That’s definitely a misconception that I hear from a lot of parents.”