By: Frederick (Rick) Ezekiel, PhD, Director of Equitable Learning, Health and Wellness, Centennial College, Toronto, Canada

SUMMARY

Postsecondary educators have been increasingly focused on supporting positive student mental health over the past decades. Postsecondary institutions are uniquely positioned to support a demographic of students who experience the greatest risk of first onset of mental illness as a result of the developmental trajectory of many common mental illnesses (within the 16-24 age window; Jones, 2013). Additionally, poor mental health and toxic stress have a detrimental impact on learning and academic performance. My research seeks to understand disparities in mental health outcomes among students with marginalized sociodemographic identities in Canada, and the relationship between mental health and learning with marginalized communities. Through this work, I identified that marginalized sociodemographic groups experience languishing mental health at rates 1.6 – 3.4 times that of their peers. Additionally, much of the difference in academic performance among students with marginalized sociodemographic identities was statistically explained by disparities in mental health. As we expand our focus on enhancing student mental health, we must critically examine sociocultural factors influencing disparities in mental health outcomes among postsecondary students. Of equal importance, we must examine institutional actions which could begin to address the systemic barriers and mechanisms through which these inequities emerge.

Background

Stress, Mental Health and Learning

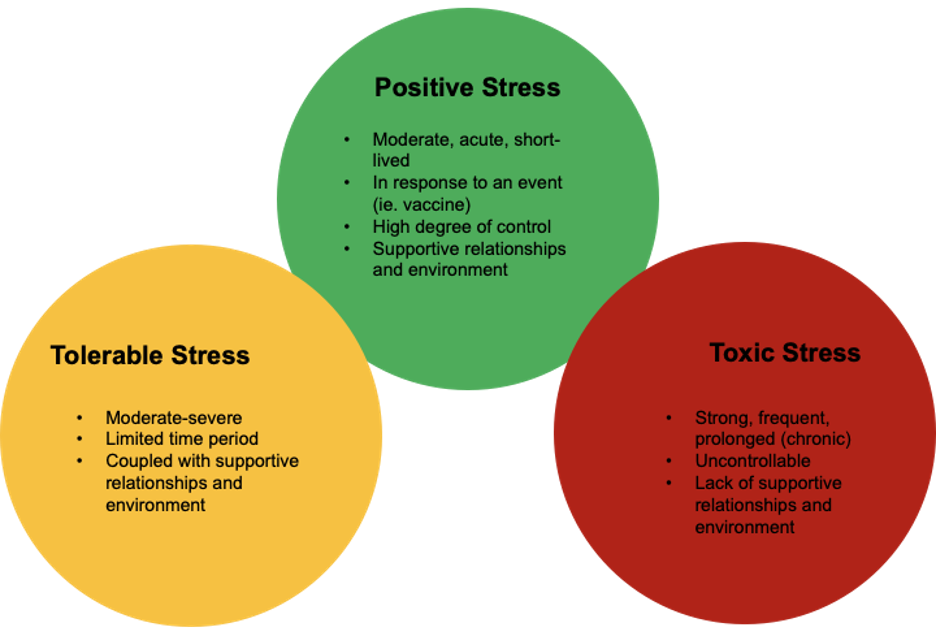

Stress is a natural part of the human condition, and can be performance enhancing at low to moderate levels. Stress is more likely to be experienced as positive or performance enhancing when we have sufficient control over a situation, perceive a reasonable ability to overcome the stressor, and have access to positive psychosocial supports and safe environments. However, at chronic and severe levels, stress can become maladaptive and lead to reduced performance outcomes, including in postsecondary learning environments.

The stress response mobilizes the sympathetic nervous system, leading to the well known fight, flight or freeze response. This response has had adaptive value over the course of human evolution, when stressors often involved reacting to immediate threats to our survival. However, the stress response undermines and utilizes limited executive cognitive functions which are necessary for learning and the demonstration of what one has learned, which can result in reduced academic performance at toxic levels (Owens et al., 2008).

Stress and Mental Health in Marginalized Sociodemographic Groups

Marginalized sociodemographic groups navigate more barriers and challenges (stressors) within our society, and postsecondary education institutions. Minority stress theory, coined by Ilan Meyer (2003), articulates empirically supported findings where marginalized sociodemographic groups experience increased risk for distress due to more frequent and deleterious experiences of discrimination, harassment, systemic oppression / barriers, stigmatization and social isolation. Common examples in postsecondary contexts include: transgender students who are misgendered by a faculty member in front of the class, ‘outing’ them and contributing to broader othering impacts; racialized students seeing racial slurs, racist graffiti, or racist posters on campus, and not seeing their identities reflected in their faculty, staff or educational leaders; students with disabilities experiencing repeated events or information that are not accessible, leading to exclusion and needing to repeatedly ask for accommodations to participate in campus life; and gay, lesbian, queer, bi-sexual, questioning students coming out to family and friends, sometimes facing rejection or unsupportive reactions from loved ones.

A key goal of my research involved examining the influence of minority stress on mental health and learning within a large sample of postsecondary education students in Canada. Marginalized and disadvantaged sociodemographic groups within myresearchincluded sexual minorities (students who do not identify as heterosexual), students who identify as transgender or gender non-binary, female-identified individuals, racial and ethnic minorities (students who identify as non-white), Indigenous students, students with disabilities, and students with diagnosed psychiatric conditions.

Risk and Resilience Within Marginalized Learners: A Strengths-Based Approach

I leveraged a strengths-based approach to understanding mental health and learning within marginalized communities in this research. Part of this approach involves positioning the deficits driving disparity within the societal and institutional systems that perpetuate systemic oppression, and NOT within the individual learners or communities who hold marginalized identities. Additionally, it is crucial to recognize the strength and resilience that marginalized learners bring into the postsecondary learning environment, having overcome significant barriers and stressors over the course of their development to make it to college or university in the first place.

Significant work has examined community-specific resilience factors which serve as protective factors within marginalized communities. These community resilience factors include:

- Community connection and support (Wexler et al., 2009; Kirmayer et al., 2011)

- Acknowledgement of and collective meaning making related to experiences with discrimination or oppression, and galvanized purpose toward collective action (French et al., 2020; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Meyer, 2015)

- Human rights protections and equitable legal recognition / protections for identity representation and full inclusion; and,

- Cultural identity, connection to language & land within Indigenous communities (Kirmayer et al., 2011).

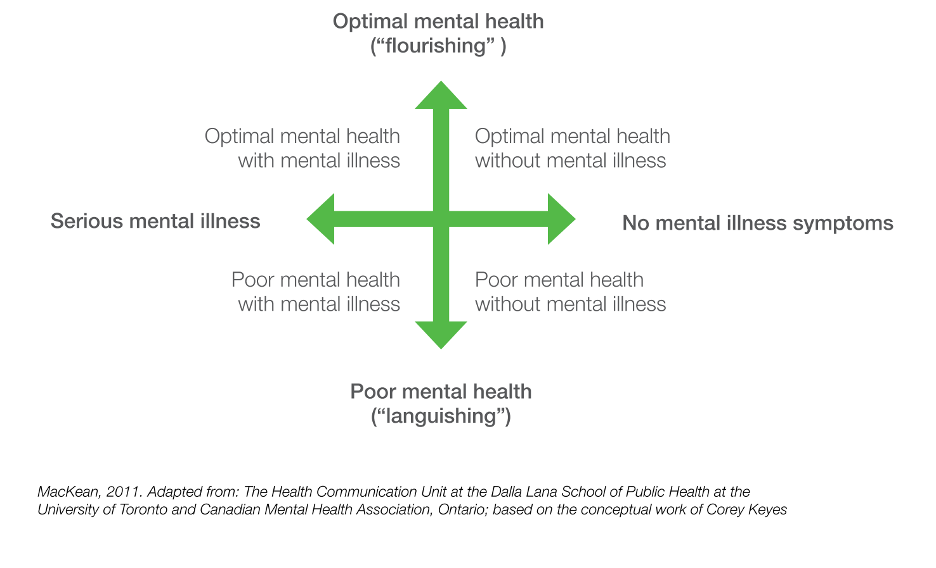

The Mental Health Continuum (Keyes, 2003) is a measure of mental health from positive psychology, which captures processes contributing to wellbeing that might be impacted by marginalization or othering, as well as factors that might confer community resilience such as those described above. Additionally, the measure is informed by the dual continuum of mental health, acknowledging that learners can experience flourishing or languishing mental health coupled with both a presence or absence of mental illness (MacKean et al., 2011). For these reasons, I selected this as the measure of choice utilized within my research.

Research Findings

Integrating my research findings, the conceptual model above has guided my research questions and analysis, to investigate relationships between holding a marginalized identity, mental health, and academic performance in postsecondary students. It provides a simple and overarching conceptual explanation of the research findings below.

The research findings presented below draw from analysis of the National College Health Assessment (NCHA) 2016 Canadian Reference group, which included 42,642 students from 42 postsecondary institutions (colleges and universities) across Canada (ACHA, 2016; Ezekiel, In Press).

Mental Health Among Marginalized Sociodemographic Groups

Overall findings – my research demonstrated that:

- Postsecondary learners with marginalized sociodemographic identities experienced languishing mental health at 1.6-3.4 times the frequency of peers not marginalized on the same binary; and,

- Disparities in mental health statistically explained much of the measurable differences in academic performance among learners with marginalized identities

A note for my fellow quantitative researchers / data nerds: These findings identified that mental health partially or fully statistically mediated the relationship between identifying with a marginalized sociodemographic group and reduced academic performance within a structural equation model.

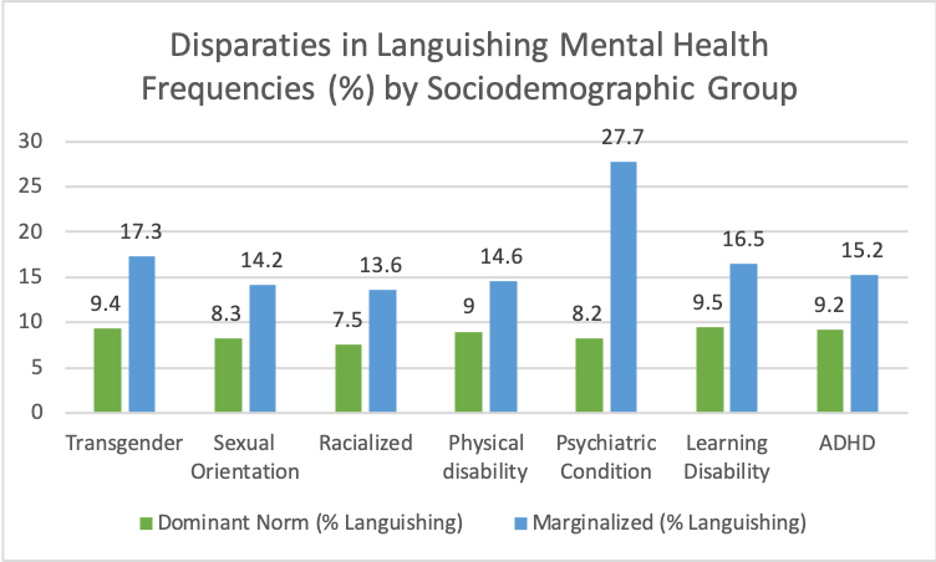

Disparities in Languishing Mental Health by Sociodemographic Group

Within this sample, students holding a marginalized identity experienced languishing mental health at rates 1.6-3.4 times those of their peers who were not marginalized on the same binary. The chart below highlights proportions of group members identified as having languishing mental health within each identity binary. The green bars show the proportion of Individuals identifying with the dominant norm (e.g. cisgender; white; or not having a diagnosed psychiatric condition) who had languishing mental health, and the blue bars show the proportion of individuals who held marginalized identities within the binary who had languishing mental health (e.g. transgender; racialized; or having a diagnosed psychiatric condition). This visualizes significant mental health disparities, with members of marginalized sociodemographic groups experiencing languishing mental health at greater frequencies.

Note: chi-squared analysis confirmed that all frequency differences in mental health reported below were statistically significant at thresholds of p < 0.001.

Important in reviewing these findings from a strengths-based perspective is to recognize that while there were significant and large disparities in the proportion of students experiencing languishing mental health among students with marginalized identities, there were also significant numbers of individuals with marginalized identities experiencing flourishing mental health. We must interpret these disparities as reflective of systemic and deleterious stressors uniquely impacting marginalized communities (e.g. systemic and overt racism on and off campus, barriers to access and inclusion in the learning environment and campus life among students with disabilities, homophobia and transphobia on campus and in broader communities), rather than reflective of deficits within individuals who hold marginalized identities (an attribution that is not supported by the empirical neurodevelopmental or psychological research in this space).

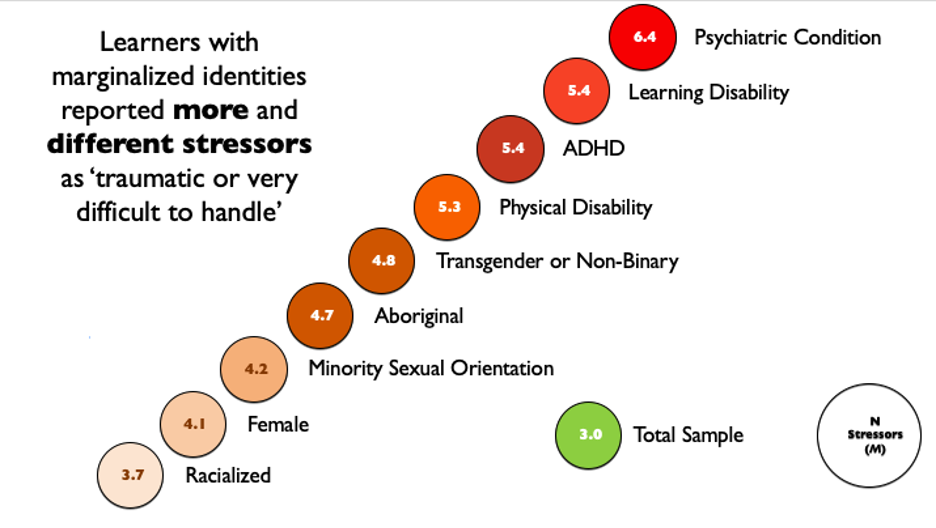

Additionally, students identifying with marginalized sociodemographic groups reported different, and more stressors as ‘traumatic or very difficult to handle’ relative to the overall sample, underscoring the notion of increased frequency of experiencing deleterious stressors among marginalized communities in alignment with predictions from minority stress theory.

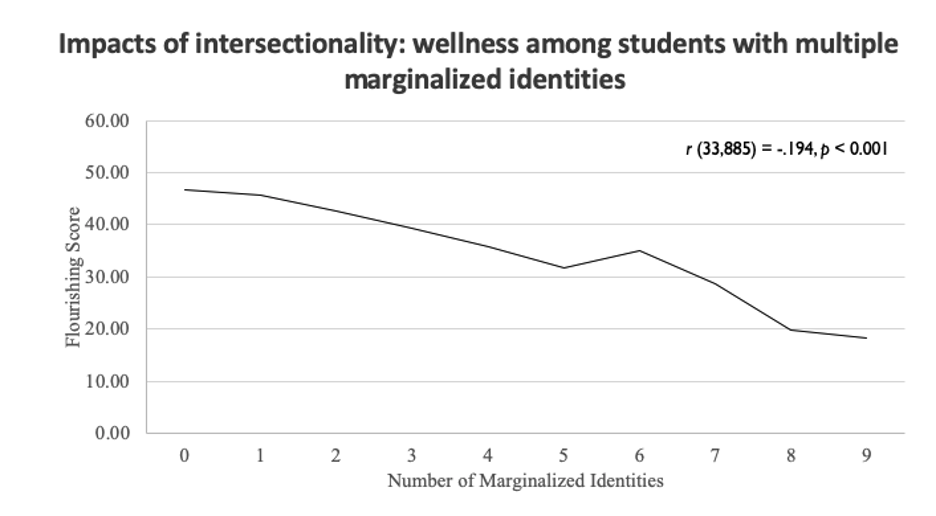

Impacts of Intersectionality

The concept of intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe the interactive effects of holding multiple marginalized identities, often leading to disparities and experiences with oppression that are more severe and complex than additive effects of disparity across two binaries. In examining whether holding multiple marginalized identities led to additive stress and reduced mental health, I identified a significant, negative correlation between the number of marginalized identities a student held, and their mental health (r (33,885) = -.194, p < 0.001). In other words, students who held more marginalized identities tended to report lower mental health.

For the purposes of this blog, I’ve summarized research findings at a very high-level. All summary statistics or narrative findings reported above were supported by robust quantitative analysis, and results that were statistically significant at rigorous thresholds. Detailed statistics and additional information on methodology can be reviewed within my complete dissertation (available on request, or through the University of Toronto thesis repository in summer 2021).

There are significant limitations and cautions to utilizing quantitative approaches to understand experiences of marginalized communities who have low representation within a given population and sample. To this end, I attempted to disaggregate data to ensure disparities were not ‘averaged out’ due to low representation. However, survey tools and quantitative analyses still wash out unique experiences of minority voices as they are normalized against experiences of the majority population. For example, the list of stressors reported as ‘traumatic or very difficult to handle’ included common experiences such as academic difficulties, career related issues, interpersonal conflict, financial difficulties, sleep difficulties and chronic health issues. They did not, however, included stressors unique to marginalized communities that could impact overall wellbeing (e.g. navigating a gender transition or being regularly misgendered among transgender students; seeing racial slurs on campus, in social media, and through other avenues, or participating in advocacy for racial justice among racialized learners; and navigating an often ongoing coming out process among sexual minorities, including fear of and experiences with family and friend rejections). In this way, quantitative research can reinforce a ‘tyranny of the majority’ by erasing experiences of minority voices.

It is imperative that we recognize these limitations, seek to leverage mixed methods approaches to more deeply understand experiences of individuals with marginalized identities, and develop representative and inclusive quantitative research tools to better understand experiences of learners with marginalized identities. Additionally, we as educators and student affairs practitioners must deeply engage the voices of learners with marginalized identities, and ensure those voices are guiding our actions to begin to reduce the disparities highlighted in my research above.

Implications and Promising Institutional Actions

My research findings further underscore that postsecondary institutions have a moral and educational imperative to create conditions where all learners have the opportunity to thrive, particularly those experiencing heightened stress as a result from marginalization or developmental vulnerabilities.

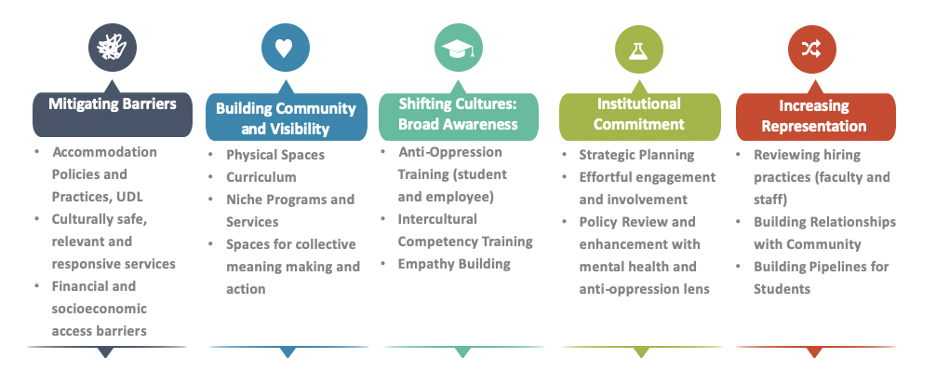

Recognizing the significant disparities identified in mental health among learners with marginalized identities and subsequent impacts on learning, it is imperative that postsecondary education institutions engage in multi-level action at the research, policy and practice levels to mitigate the undue barriers and stressors driving these outcomes. The graphic below summarizes promising priorities for institutional action to promote wellbeing, equity and learning among marginalized sociodemographic groups in postsecondary education.

As we continue to examine strategies to enhance mental health within our postsecondary communities, it is critical that we take a proportionate universality approach – focusing on universal actions enhancing wellbeing and learning for all, with proportionately more intensive supports and efforts focused on those experiencing the greatest risk due to marginalization. I will highlight some of my own reflections on promising areas for institutional action based on my policy and practice work within higher education.

Mitigating Barriers

Most postsecondary education institutions in North America are guided by legislation focused on access for learners with disabilities, as well as human rights law offering legal protection against discrimination on protected grounds. While these are critical in establishing foundational rights and protections, they more often assist in guiding against overt oppression, whereas many of the barriers and stressors captured under minority stress theory focus on day-to-day, insidious, and deleterious experiences of othering and exclusion from the dominant norms within postsecondary institutions. The process of accommodation itself is often onerous, time consuming, and stigmatizing, involving some degree of ‘outing’ of a student to access the support needed to access learning.

For example, students with learning disabilities are asked to engage with multiple professionals through very time consuming and often clunky processes (often starting with meeting with an accessible learning advisor / counsellor, followed by third party psychoeducational assessment with external providers often associated with financial and administrative burdens, followed by follow-up meetings with the psychologist and accessible learning advisor) to support their need for accommodation, when often the most pressing need is more time. This creates an ironic paradox when our institutional processes add additional stress, time, and cognitive demands for students with disabilities when their most important need is often time and attention to engage with learning.

To continue to mitigate stressors unduly impacting marginalized learners, it is critical that institutions continue to work to deeply embed universal and inclusive design for learning within the curriculum, co-curriculum, and professional service environment (Meyer & Rose, 2002). Additionally, investing in culturally safe, relevant, and responsive mental health services meeting the unique needs of marginalized learners will be critical to address these challenges. Some examples include:

- Universal: focus on just-in-time service delivery models, eliminating wait lists and barriers to engagement in mental health services when students demonstrate readiness to engage;

- Proportional and targeted: dedicated, culturally relevant wellbeing for Indigenous learners in connection with community; establishment of subject matter expertise and inclusion of professionals with lived experience on medical and mental health care teams (e.g. transgender care teams, sexual violence and trauma-informed care expertise, competency in offering mental health supports for LGBQ students).

Building Community and Visibility

Within my research and the broader literature, sense of belonging has been identified as a promising protective factor mediating the negative relationship between stress and academic performance. Creating spaces for collective meaning making, connection, and gathering can be critical in supporting minority community resilience on postsecondary campuses. This can include institutionally (faculty / staff) supported student groups (e.g. cultural and racial or ethnic community groups; LGBTQ2S+ spaces and organizing groups; physical spaces for Indigenous students, faculty and staff; peer mentorship opportunities and programming supporting unique needs of students with disabilities).

Additionally, it is critical that institutions promote visibility (authentically, and with voices of marginalized community members at the forefront) at the broader institutional level. Consider the topics covered in lectures, representation among high-profile speakers and panels, physical spaces, art, architecture, landscaping. Within student affairs, representation in programming offered (e.g. orientation programming) is a critical opportunity to demonstrate the degree to which students from marginalized communities see themselves, their identities, their cultures and values represented within the organizational fabric during transition into college and university.

Shifting Cultures: Broad Awareness

As learning institutions, we have a significant opportunity to increase knowledge related to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) among our student, faculty and staff populations, to the benefit of our wider communities. Recognizing limitations of curricular content related to colonization, EDI, and anti-oppression in the K-12 system, institutions have an opportunity to expand student awareness of systemic factors contributing to inequities at multiple levels within our society. As institutions seek to build and implement anti-oppression training programs, promising practices include:

- Hiring curriculum developers and trainers who have lived experience and subject matter expertise and compensate them fairly;

- Focusing on co-construction models, ensuring that students and employees with marginalized identities are actively involved with and driving the content of the training; and,

- Training individuals in positions of influence first, to realize broader benefits of knowledge and skills within the organization (e.g. student leaders, administrative leaders).

Institutional Commitment

It is critical that institutions ensure EDI issues are identified as priorities at the highest levels of the organization. EDI and anti-oppression should be identified as core values of the organization, and key priorities across strategic planning frameworks. Additionally, anti-oppression rubrics or intentional review structures should be embedded within organizational policy review frameworks, ensuring that EDI and anti-oppression are top of mind as administrators review organizational policies (whether they be focused on grading, facilities, or employee recruitment and compensation).

Increasing Representation

Critical to the success of all the priorities and actions identified above involves increasing representation of marginalized communities who are under-represented within student, faculty and staff populations, and ensuring their active inclusion within the institutional fabric and at decision making tables. Increasing representation among underrepresented groups should be identified as a priority in faculty, staff, and senior administration recruitment and hiring processes. Additionally, expanding access and representation among students should be critical considerations in domestic and international recruitment strategies.

Across employee and student groups, institutions must focus on authentically building relationships with marginalized communities through their recruitment efforts. Investing back in marginalized communities through services, mentorship programs, participatory action research, and educational and learning opportunities grounded in articulated community needs can be effective strategies to increase authentic relationships with marginalized and underrepresented communities. Additionally, institutions must consider barriers resulting from systemic oppression within our broader societies preventing access, including significant socioeconomic disparities. Educational access and financial means might be significant factors at play for capable prospective students and employees. Building pathways to study and employment, with necessary financial supports, mentorship, education and credential upgrading, and access opportunities are critical to combatting broader oppressive structures at play that could influence underrepresentation within postsecondary institutions.

Conclusions

Student affairs practitioners and educators have become increasingly aware of student mental health and the impacts of mental health on learning. Additionally, conversations about equity, diversity and inclusion have become more salient in many institutions stemming from long overdue social movements and broader societal conversations. A core goal of my research was to demonstrate utilizing a large, empirical research design the impacts of marginalization on wellbeing and learning among postsecondary students in Canada. I hope these data, coupled with promising practices for action, spark ongoing investigation and action among educators in the postsecondary sector, ensuring we work against perpetuating the insidious oppressive structures within our broader societies. With intention and effort, we have the capacity as educators and institutions to become equity-promoting tools for the students and communities we serve, which has and will continue to be the motivating goal of this work.

Rick Ezekiel (he/him) is the Director of Equitable Learning, Health and Wellness at Centennial College (Toronto, Canada), and completed his PhD at The University of Toronto (OISE) in December 2020. At the centre of Rick’s professional and scholarly work is a core passion to enhance the role education can play in promoting equitable lifespan development outcomes for learners within our broader communities and society. Rick is a cisgender, queer man of European (settler) ancestry, respectfully and gratefully doing research and work within the traditional territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, in the Dish with One Spoon Treaty Region.

References

American College Health Association (2016). National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2016. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. doi:10.2307/1229039

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

Ezekiel, F. (In Press). Mental Health and Academic Performance in Postsecondary Education: Sociodemographic Risk Factors and Links to Childhood Adversity, PhD Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

French, B. H., Lewis, J. A., Mosley, D. V., Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Chen, G. A., & Neville, H. A. (2020). Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 14-46.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Haidt, J. (2003). Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC, US. http://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2

Jones, P. B. (2013). Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(54), 5–10. http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164

Kirmayer, L. J., Dandeneau, S., Marshall, E., Phillips, M. K., & Williamson, K. J. (2011). Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(2), 84-91.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol Bull., 129(5), 674–697. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.011.Innate

Owens, M., Stevenson, J., Norgate, R., & Hadwin, J. A. (2008). Processing efficiency theory in children: working memory as a mediator between trait anxiety and academic performance. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(4), 417–30. http://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701847823

Post-Secondary Student Mental Health: Guide to a Systemic Approach. (2013). Vancouver, BC.

Wexler, L. M., DiFluvio, G., & Burke, T. K. (2009). Resilience and marginalized youth: Making a case for personal and collective meaning-making as part of resilience research in public health. Social Science and Medicine, 69(4), 565–570. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.022

Yerkes, R., & Dodson, J. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459–482.

Copyright Acknowledgment

High-level research findings shared in this blog are produced pre-publication (with submission to peer-reviewed journals underway). Please seek written permission before reproducing these data or images (fezekiel1@gmail.com), and if referencing this work, in addition to this blog post, please reference my dissertation (Ezekiel, In Press) as the original source of these research findings.

The American College Health Association – National College Health Assessment II – Canadian Reference Group survey tool is copyrighted material by the American College Health Association (ACHA). The National College Health Assessment raw data referenced in this blog, were used in my original research with permission based on a formal request to the ACHA, who provided that data for the purposes of my dissertation research. The opinions, findings, and conclusions presented/reported in this post are those of the author, and are in no way meant to represent the corporate opinions, views, or policies of the ACHA. The ACHA does not warrant nor assume any liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information presented in this article/presentation.

Reblogged this on Rick's Road to Boston: 2021 and commented:

Taking a little hiatus from my running posts to share this guest blog I wrote over the past couple weeks on some of my PhD research, highlighting the relationship between mental health and learning among postsecondary students with marginalized identities, as well as promising institutional actions to promote wellbeing for equity deserving communities. Give it a read, and I’ll be back with some related content on running as a tool to manage stress and anxiety later this week.

An excellent snapshot of your research Rick and welcome addition to the collective knowledge of learner mental health, resilience, and the strategies that can support student success. Understanding the disproportionate and cumulative impact of stress and trauma on learners from equity-seeking groups is critically needed in our work and I’m grateful for your work and voice.